Royal titles in the United Kingdom carry a rich tapestry of history, embodying centuries of tradition while adapting to the changing landscape of the modern world. This article delves into the structure of these titles, focusing on significant changes made during the 20th and 21st centuries, and how these rules affect current royals.

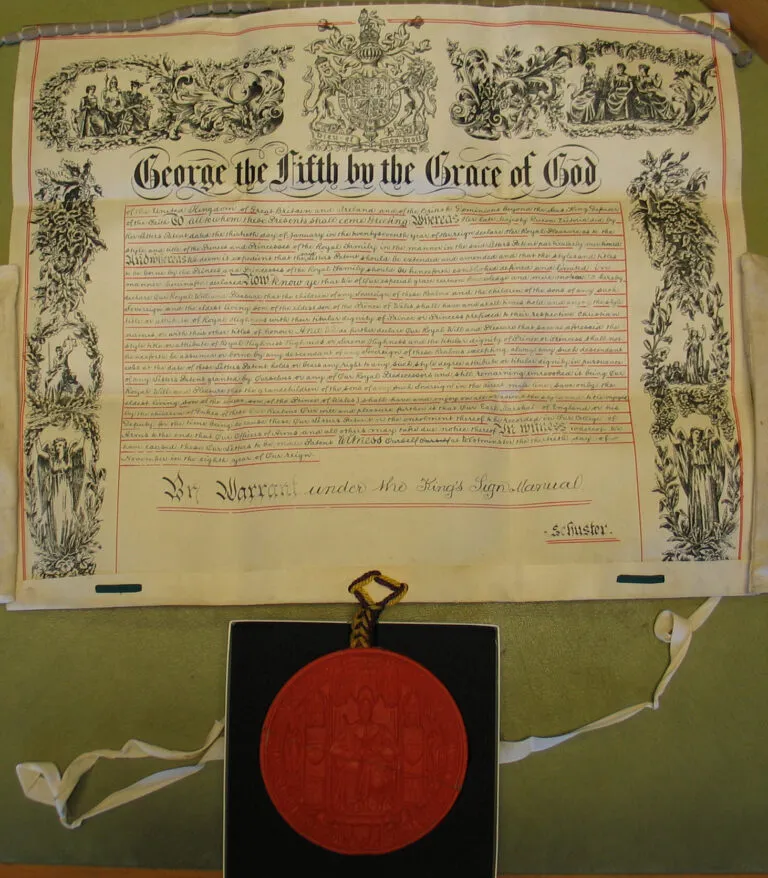

The Foundations: Letters Patent of 1917

The framework for today’s royal titles was significantly shaped by the Letters Patent issued by King George V in 1917. This document was pivotal in redefining who in the royal family would be styled with “His or Her Royal Highness” (HRH) and as a prince or princess. Specifically, the 1917 Letters Patent restricted these styles to:

- The sons and daughters of a sovereign.

- The male-line grandchildren of a sovereign.

- The eldest living son of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales.

This move was partly in response to the anti-German sentiment of World War I, aiming to streamline the monarchy and solidify its British identity by reducing the number of royals with German titles.

Notice that the definitions talk about “a sovereign”, not “the sovereign”. This means that when the sovereign changes, no-one will lose their royal title (for example, Prince Andrew is still the son of a sovereign, even though he is no longer the son of the sovereign). However, people can gain royal titles when the sovereign changes – we will see examples below.

Extension by George VI in 1948

Understanding the implications of the existing rules as his family grew, King George VI issued a new Letters Patent in 1948 to extend the style of HRH and prince/princess to the children of the future queen, Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II). This was crucial as, without this adjustment, Princess Elizabeth’s children would not automatically have become princes or princesses because they were not male-line grandchildren of the monarch. This ensured that Charles and Anne were born with princely status, despite being the female-line grandchildren of a monarch.

The Modern Adjustments: Queen Elizabeth II’s 2012 Update

Queen Elizabeth II’s update to the royal titles in 2012 before the birth of Prince William’s children was another significant modification. The Letters Patent of 2012 decreed that all the children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales would hold the title of HRH and be styled as prince or princess, not just the eldest son. This move was in anticipation of changes brought about by the Succession to the Crown Act of 2013, which ended the system of male primogeniture, ensuring that the firstborn child of the Prince of Wales, regardless of gender, would be the direct heir to the throne. Without this change, there could have been a situation where Prince William’s first child (and the heir to the throne) was a daughter who wasn’t a princess, whereas her eldest (but younger) brother would have been a prince.

Impact on Current Royals

- Children of Princess Anne: When Anne married Captain Mark Phillips in 1973, he was offered an earldom but declined it. Consequently, their children, Peter Phillips and Zara Tindall, were not born with any titles. This decision reflects Princess Anne’s preference for her children to have a more private life, albeit still active within the royal fold.

- Children of Prince Edward: Initially, Prince Edward’s children were styled as children of an earl, despite his being a son of the sovereign. Recently, his son James assumed the courtesy title Earl of Wessex, when Prince Edward was created the Duke of Edinburgh. His daughter, Lady Louise Windsor, continued to use the same style as she did before her father became duke – the style for the daughter of a duke being identical to that for the daughter of an earl.

- Children of Prince Harry: When Archie and Lilibet were born, they were not entitled to princely status or HRH. They were great-grandchildren of the monarch and, despite the Queen’s adjustments in 2012, their cousins – George, Charlotte and Louis – were the only great-grandchildren of the monarch with those titles. When their grandfather became king, they became male-line grandchildren of a monarch and, hence, a prince and a princess. It took a while for those changes to be reflected on the royal family website. This presumably gave the royal household time to reflect on the effect of the children’s parents withdrawing from royal life and moving to the USA.

Special Titles: Prince of Wales and Princess Royal

- Prince of Wales: Historically granted to the heir apparent, this title is not automatic and needs to be specifically bestowed by the monarch. Prince Charles was created Prince of Wales in 1958, though he had been the heir apparent since 1952. Prince William, on the other hand, received the title in 2022 – just a day after the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

- Princess Royal: This title is reserved for the sovereign’s eldest daughter but is not automatically reassigned when the previous holder passes away or when a new eldest daughter is born. Queen Elizabeth II was never Princess Royal because her aunt, Princess Mary, held the title during her lifetime. Princess Anne currently holds this title, having received it in 1987.

The Fade of Titles: Distant Royals

As the royal family branches out, descendants become too distanced from the throne, removing their entitlement to HRH and princely status. For example, the Duke of Gloucester, Duke of Kent, Prince Michael of Kent and Princess Alexandra all have princely status as male-line grandchildren of George V. Their children are all great-grandchildren of a monarch and, therefore, do not all have royal styles or titles. This reflects a natural trimming of the royal family tree, focusing the monarchy’s public role on those directly in line for succession.

Conclusion

The evolution of British royal titles reflects both adherence to deep-rooted traditions and responsiveness to modern expectations. These titles not only delineate the structure and hierarchy within the royal family but also adapt to changes in societal norms and the legal landscape, ensuring the British monarchy remains both respected and relevant in the contemporary era.