The term “royal” often conjures images of crowns, palaces, and centuries-old traditions. However, what exactly constitutes a “royal” can vary depending on the context. In the modern British monarchy, there are several ways to define who is considered a royal. This article will explore three such definitions: holding the style “His/Her Royal Highness” (HRH), being a member of the royal family by descent or marriage, and being a working royal. Each of these definitions offers a different perspective on what it means to belong to the British royal family.

1. Holding the Style HM or HRH

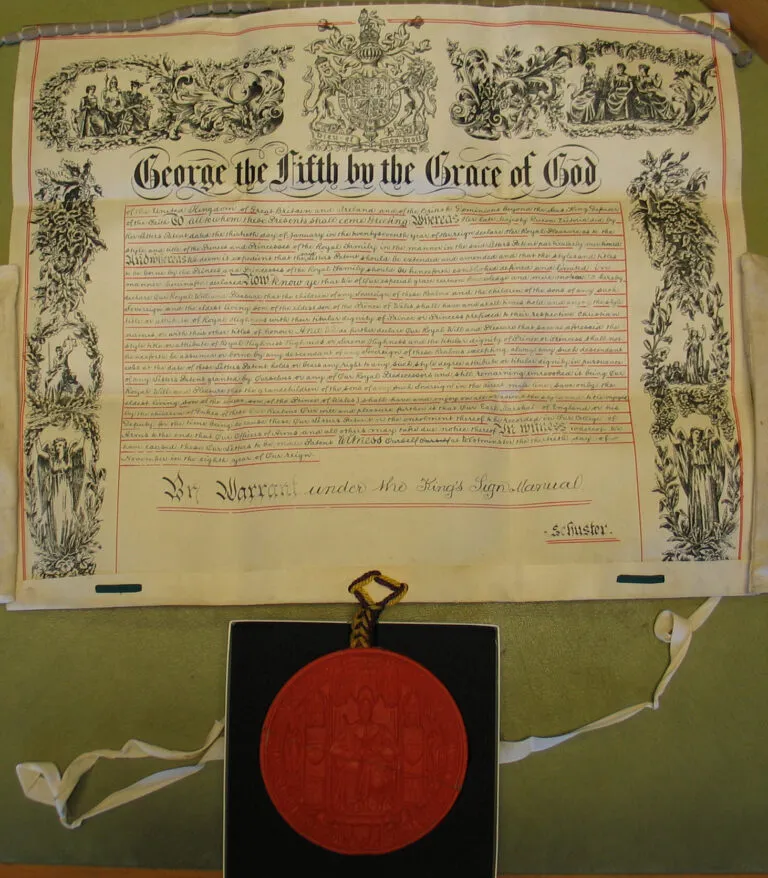

One of the most formal and legally recognised ways to be considered a royal is by holding the style “His/Her Majesty” (HM) or “His/Her Royal Highness” (HRH). This designation has its roots in British legal tradition, specifically in the Letters Patent issued by King George V in 1917 and later updated by Queen Elizabeth II in 2012.

Historical Context

The Letters Patent of 1917 were issued by King George V during a time of anti-German sentiment during World War I. The letters were designed to limit the number of people entitled to the style HRH, focusing the title on the closest relatives of the monarch. Under these guidelines, only the children of the sovereign, the children of the sovereign’s sons, and the eldest living son of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales were entitled to the HRH style.

In 2012, Queen Elizabeth II issued a new Letters Patent to extend the HRH title to all children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales, rather than just the eldest living son. This change ensured that all of Prince William’s children, not just Prince George, would hold the HRH title.

Current Royals with HRH Style

As of 2024, the individuals entitled to the HRH style are:

- Charles III

- Camilla (the wife of the King)

- Prince William, Prince of Wales (eldest son of the King)

- Catherine, Princess of Wales (wife of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince George of Wales (eldest son of the Prince of Wales)

- Princess Charlotte of Wales (daughter of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince Louis of Wales (youngest son of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex (younger son of the King)

- Meghan, Duchess of Sussex (wife of the Duke of Sussex)

- Prince Archie of Sussex (son of the Duke of Sussex)

- Princess Lilbet of Sussex (daughter of the Duke of Sussex)

- Princess Anne, The Princess Royal (daughter of Elizabeth II)

- Prince Andrew, Duke of York (younger son of Elizabeth II)

- Princess Beatrice, Mrs Mapelli Mozzi (elder daughter of the Duke of York)

- Princess Eugenie, Mrs Brooksbank (younger daughter of the Duke of York)

- Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh (youngest son of Elizabeth II)

- Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh (wife of the Duke of Edinburgh)

- James, Earl of Wessex (son of the Duke of Edinburgh)

- Lady Louise Windsor (daughter of the Duke of Edinburgh)

- Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester (grandson of George V)

- Birgitte, Duchess of Gloucester(wife of the Duke of Gloucester)

- Prince Edward, Duke of Kent (grandson of George V)

- Katharine, Duchess of Kent (wife of the Duke of Kent)

- Princess Alexandra (granddaughter of George V)

- Prince Michael of Kent (grandson of George V)

- Princess Michael of Kent (wife of Prince Michael of Kent)

The Duke and Duchess of Sussex and the Duke of York have agreed not to use their HRH styles except when on official royal family business.

James, Earl of Wessex and Lady Louise Windsor do not use the princely titles they are entitled to or their HRH styles.

Prince Archie and Princess Lilibet are entitled to HRH styles under the 1917 Letters Patent, but they have never yet used these styles.

2. Being a Member of the Royal Family

Another definition of being a royal is broader and includes anyone who is a direct descendant of Queen Elizabeth II or who is married to one of her descendants. This definition encapsulates a larger group, reflecting the extended royal family, which may include individuals who do not hold the HRH style but are nonetheless considered part of the royal family by virtue of their lineage or marriage.

Current Members of the Royal Family

As of 2024, the following individuals are considered members of the royal family by descent or marriage:

- Charles III

- Camilla (wife of the King)

- Prince William, Prince of Wales (eldest son of the King)

- Catherine, Princess of Wales (wife of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince George of Wales (eldest son of the Prince of Wales)

- Princess Charlotte of Wales (daughter of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince Louis of Wales (youngest son of the Prince of Wales)

- Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex (youngest son of the King)

- Meghan, Duchess of Sussex (wife of the Duke of Sussex)

- Princess Archie of Sussex (son of the Duke of Sussex)

- Princess Lilibet of Sussex (daughter of the Duke of Sussex)

- Princess Anne, The Princess Royal (sister of the King)

- Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence (husband of the Princess Royal)

- Peter Phillips (son of the Princess of Wales)

- Savannah Phillips (daughter of Peter Phillips)

- Isla Phillips (daughter of Peter Phillips)

- Zara Tindall (daughter of the Princess Roya)

- Mike Tindall (husband of Zara Tindall)

- Mia Tindall (daughter of Zara Tindall)

- Lena Tindall (daughter of Zara Tindall)

- Lucas Tindall (son of ZaraTindall)

- Prince Andrew, Duke of York (younger brother of King)

- Princess Beatrice, Mrs Mapelli Mozzi (eldest daughter of the Duke of York)

- Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi (husband of Princess Beatrice)

- Sienna Mapelli Mozzi (daughter of Princess Beatrice)

- Princess Eugenie, Mrs Brooksbank (youngest daughter of the Duke of York)

- Jack Brooksbank (husband of Princess Eugenie)

- August Brooksbank (eldest son of Princess Eugenie)

- Ernest Brooksbank (youngest son of Princess Eugenie)

- Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh (youngest brother of the King)

- Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh (wife of the Duke of Edinburgh)

- Lady Louise Windsor (daughter of the Duke of Edinburgh)

- James, Earl of Wessex (son of Duke of Edinburgh)

This list represents the extended royal family, including younger generations who may not hold the HRH title but are nonetheless royals by descent.

3. Being a Working Royal

A more functional definition of being a royal involves being a “working royal.” This term refers to those members of the royal family who actively perform duties on behalf of the Crown. These duties include public appearances, charitable work, and representing the monarchy both within the United Kingdom and abroad. Under the reign of King Charles III, the number of working royals has been streamlined to focus on those closest to the line of succession.

Current Working Royals

As of 2024, the working royals under King Charles III are:

- Charles III

- Camilla

- Prince William, Prince of Wales

- Catherine, Princess of Wales

- Princess Anne, The Princess Royal

- Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence (husband of the Princess Royal)

- Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh

- Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh

- The Duke of Gloucester

- The Duchess of Gloucester

- The Duke of Kent

- Princess Alexandra

These individuals are the primary faces of the British monarchy, regularly engaging with the public and fulfilling official duties. The focus on a smaller group of working royals is part of Charles III’s vision for a more modern and efficient monarchy.

Conclusion

The concept of being a “royal” in the British context is multifaceted and can be defined in several ways. Whether through the formal title of HRH, lineage, marriage, or active service to the Crown, each definition captures a different aspect of royal life. Understanding these distinctions provides a deeper insight into the structure and functioning of the British royal family as it continues to evolve in the 21st century.